Leading from the middle - when Exec aren't driving

A great question emerged in conversation with two clients recently: “is our Executive the right place to focus for developing our capability?” My surprising answer was “maybe not – working on the third layer might give the most change, the most quickly.”

I co-wrote a book chapter in 2016 on Leadership in the Networked Museum, whose first two sentences are,

Museums Victoria, Australia's largest museum group, operates as a networked organisation, in which "independent people and groups act as independent nodes, link across boundaries, to work together for a common purpose; it has multiple leaders, lots of voluntary links and interacting levels." This approach is the antithesis of the hierarchical, command-and-control, compartmentalized, top-down management practice that is still widespread in the museum sector.

The then CEO, Dr Patrick Greene, had instituted this model of management twelve years prior. When I started in 2013, it was eerily familiar from my background as a project director: this was to an organisation what contemporary project management methods were to leading major design and construction projects. In both, the key leadership position is the one in the middle, memorably described to me as “halfway between the coalface and the Board”.

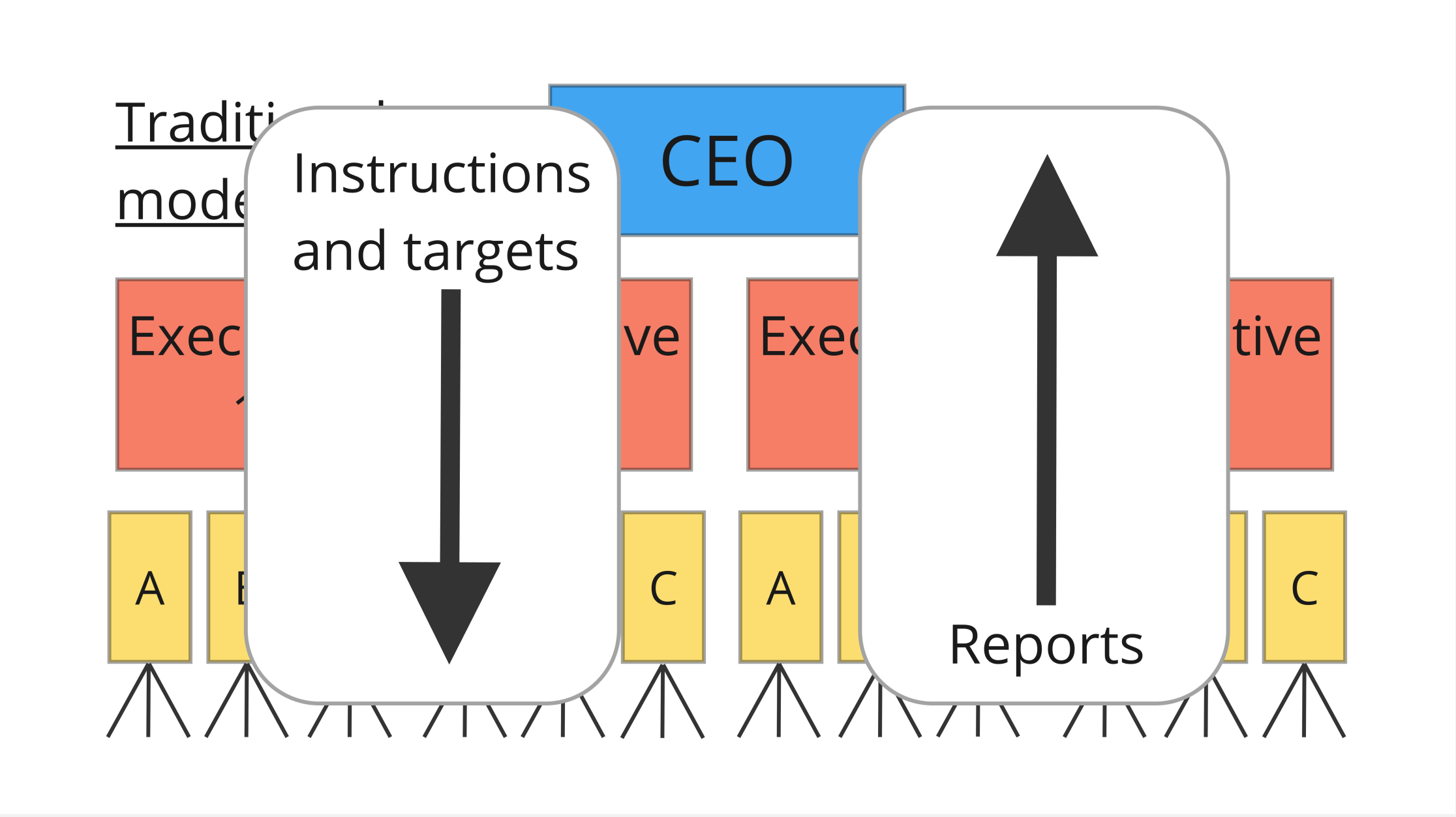

How is it different? Here's the traditional model:

Traditional organisational structure

We are all pretty familiar with this. Looks nicely ordered: the Executives each have some Senior Managers – the yellow boxes - who each manage a cluster of business units. For example a CMO on Executive might have individual units for Social Media, Marketing and Communications. But in practice, the Senior Managers in the middle of the organisation often become

A postal service between Exec and the front line

A translation service between Strategy and Operations

Over-connected up and down

Under-connected laterally

This is how it goes wrong: silos passing documents up and down.

How many times have you seen projects go wrong because of an up/down issue, and how many times for a lateral issue? In fifteen years of project and departmental debriefs, I would say issues summarised as “my department wasn’t consulted by your department” sit behind well over half of project failures. And when it doesn’t work, where does blame get pushed? That’s right, up or down: “The team were low-skilled” or “The Exec didn’t understand the reality of operations”.

But doesn't it work if 'everyone's a leader'?

In recent years there’s been a lot of attention on the idea that regardless of your position in the structure, you should be leading those around you. I would say this places the responsibility of resolving systemic problems on individuals, and contributes to workplace stress and organisational inefficiency. We should not expect individuals to lead the way out of a maze when it’s possible to remove the maze.

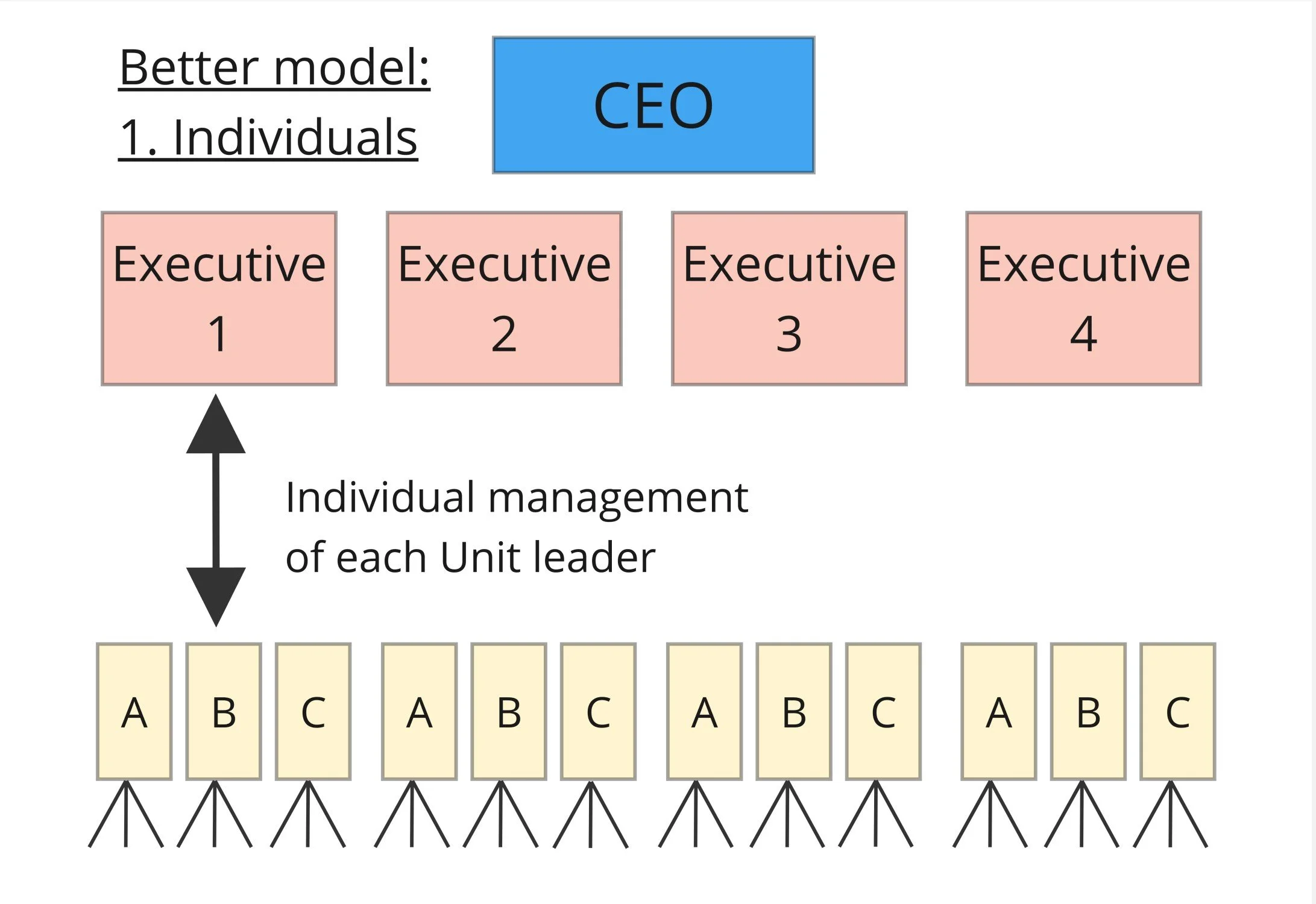

Better: design solo and team accountabilities

First, define what individual Executives are responsible for. The CMO has got to be the final work on Brand. The CFO must be the final word on Finance. In terms of implementing a media buy, or facilitating an audit review of accounts payable, they are going to direct their respective managers to get on with it. This is the bit that looks like old-school Taylorism:

First form of clarity - define solo accountabilities

But also. Be clear about accountabilities as a team. In every position description, have a section for “Joint Accountabilities as a part of the [Executive/Leadership] team”

For Executive, these might include

Take collective responsibility for the health and safety of our workforce, including creating achievable targets in line with capabilities

Take clear, timely collective decisions and communicate them transparently to the entire organisation

Actively re-prioritise organisational activity as required, with a singular collective voice

And for leadership team, this might include:

Actively collaborate across departmental lines to ensure organisational success

Consider and consult peers before seeking decisions from Executive

Second form of clarity: define team accountabilities

That’s the mechanics. But where this approach comes into its power is in consideration of the collective culture. Ever seen a rally car from inside the vehicle? The navigator is holding the map and calling instructions. These are instruction for the upcoming terrain. They have the route to the destination in their hands, and they are informing with foresight. The driver is hearing the instructions and is controlling the car. They have synergy and trust; they succeed or fail together. But the driver never looks at the map. And the navigator never grabs the wheel.

In this model, the Executive vacates the driving seat. They do not put their hands on the wheel. The Leadership team is driving the organisation. The Executive has the map.

This metaphor isn’t perfect. But in this networked model, the Executive is focused on

frameworking the organisation (translating strategy into implementation) on a quarterly / annual timescale

keeping that framework aligned with conditions in the outside world - foresight

mentoring and coaching the Leadership team – and moving on the people that don’t thrive in this model

receiving and acting on information pushed upwards to them from Leadership team

While the leadership team is

Leading the organisation’s activities on a day/week/month/quarter timescale

Actively problem solving and innovating for the whole organisation

Creating the conditions and insight necessary for Executive to make clear and timely decisions

The advantages of this system are clear. First of all it acknowledges reality - work today is rarely a Model T production line. Working across silos is a necessity.

Secondly, it gives clarity to manage performance. There are documented accountabilities for teamwork, which can be trained and managed. Often I see organisations put 'teamwork' as a value and address it solely through culture. But teamwork is a skill - it is the default operating mode for contemporary organisations. Expect it, hire for it, train for it, manage for it.

Third, it pulls Executive out of the organisation and up to strategy and partnerships. Should they know what's going on? of course. But they should only be aware and curious, not keeping their hands on the levers that they've hired the senior managers to pull.

(When i was interim COO at a huge cemetery trust, I had three experienced managers running their large teams and budgets. They were so good i could focus on bigger picture. That should be an Executive's goal. Can you take three weeks off and nothing in the operation fails?)

Fourth, it builds capability and succession options. That third layer are your Executive-in-Waiting. Build their cross-functional collaboration skills to build the team-focused Execs of the future. And build their 'present upwards, get a decision, get on with it' skills to build Execs that can work effectively with Boards.

Fifth, mistakes reduce. If Marketing is collaborating with Operations as a default, than problems like "I didn't know there'd be a scaffold going up the front of the building right before the launch weekend" (true story. bad week!)

There are more reasons of course but that's plenty for going on with.

Reflections on the model at Museums Victoria

It worked - until it didn’t. What went wrong? My views have become clearer with seven years of 20:20 hindsight.

In this model, the leadership team can become highly political – I’ll support your thing if you support mine. This tendency – like my tendency to snack on a biscuit rather than fruit – needs to be gently but actively resisted. But I think they didn’t do it hard enough and individual achievement became slightly over-prized. Also, poor performers were tolerated and so others picked up the slack: the top performing members of the leadership team spent time ‘working around’ the weaknesses in the system.

Meanwhile, the Executive didn’t seem to respond effectively to the changing external environment. As stakeholder and government sentiment shifted and year-on-year real-terms funding fell, the business model became untenable but no genuine response was developed. The Strategy was too broad and too vague; like many public-facing government functions, a clear strategy that says ‘yes’ to some things and ‘no’ to others is difficult to develop and embed. Ultimately, in 2017, a new board Chair arrived and change followed rapidly.

The take-out for me? A leadership from the middle approach is incredibly successful but only with skilled and constant vigilance from the CEO and Board. The fundamental tenets – strategy, prioritisation, accountability and culture - must be maintained.

Having worked for a retired army colonel – whose megaphone orders demanding instant obedience were the ultimate opposite to level three leadership – I’d take the networked approach any day. Higher potential for success, and lower potential for psychosocial harm.

Fin

About 25 years ago, I did a day of rally car driving. Part of it was a spin in a rally car - very fast around a Welsh hillside with an ex-pro driver. Terrifying and yet oddly boring, no thanks.

But the driving was fun. There was a corner on the circuit that i couldn't get round. Drifting the car 90 degrees right was beyond me. But oddly, I got good at spinning 270 degrees left. Sometimes, you have to go with what works, and I got a good lap time that way, to the instructor's despair and my family's laughter.

That's me for another bi-week. There's lots out there about system/networked organisations for those who're inspired into seeking them, but i hope this small exploration has been interesting. It's helped me work out my answers to those two clients.

Please let me know what you think or like and share; it's helpful for me to know what people are liking in these newsletters.

See you in another two weeks.

Paul